![Wilted Cherry Leaves [Wild Cherry - Wikimedia Commons GNU Free Documentation License Version 1.2 by Rasbak (cropped)]](https://www.quirkyscience.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Wild-Cherry-Wikimedia-Commons-GNU-Free-Documentation-License-Version-1.2-by-Rasbak-cropped.jpg) It is widely known that, to cows, wilted cherry leaves are deadly poisonous. Every cattle farmer is well acquainted with this fact. Yet, I, as a chemist, for years have wondered why. Surely it has to be a matter of chemistry, I realized. Indeed, that is the case.

It is widely known that, to cows, wilted cherry leaves are deadly poisonous. Every cattle farmer is well acquainted with this fact. Yet, I, as a chemist, for years have wondered why. Surely it has to be a matter of chemistry, I realized. Indeed, that is the case.

Cherry Fruits

Wild cherries are bitter, but to the aficionado (and I am one), the tiny fruits called wild cherries, are quite delicious, especially when made into the intensely-flavored wild cherry jelly. Curiously, these fruits contain substances that could be quite dangerous, except for the lack of substances called enzymes that would convert them into poisons.

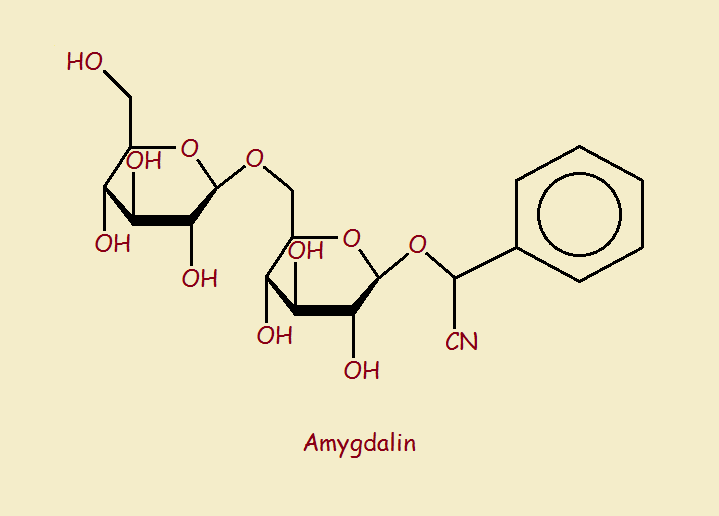

One of those chemicals is amygdalin, seen in the image below. Note—in the upper right-hand corner of the molecule—are two atoms. One of the atoms is carbon, the other nitrogen. The two are joined by a triple bond. They seem harmless enough. The combination is written simply,

-C≡N

If they are joined by a hydrogen atom (H), the result becomes,

H-C≡N

This is usually simply written HCN. But that’s the chemical formula for hydrogen cyanide!

Fortunately for fruit-lovers, wild cherries do not contain a chemical required to break off the cyanide group in the fruit itself. Such a chemical is called an enzyme. Such enzymes are, however, found in various parts of the wild cherry tree.

Other Parts of the Wild Cherry

Other Parts of the Wild Cherry

Amygdalin and related compounds (glycosides) are present throughout the cherry tree’s component parts. As for the seeds within the fruit, if these are crushed, there are enzymes present that will attack the glycosides, liberating the hydrogen cyanide. There are two steps we will elucidate here.

The first involves the enzyme prunasin beta-glucosidase. Amygdalin and the enzyme react in the presence of moisture to form D-glucose sugar plus mandelonitrile. So far, we don’t see mention of the word hydrogen cyanide, do we? But there is another enzyme present, mandelonitrile lyase. Mandelonitrile plus that enzyme, again in the presence of moisture, reacts to form benzaldehyde, and—yes—cyanide!

Wilted Cherry Leaves

Curiously, if a cherry tree is chopped, or a branch breaks (perhaps due to a summer storm)—perhaps falling to the ground—the resulting wilted leaves contain a relatively large amount of cyanide and cyanide precursors. Cyanide in wilted cherry leaves sickens and kills a cow. It ought to be mentioned that there are other plants occasionally guilty of doing the same thing (see the second reference, listed below).

Note: You might also enjoy Super Health Foods Most Health Nuts Don’t Eat

References:

AWESOME ARTICLE – loved the content – thank you so much.

Would it do the same to us? I don’t generally go around chewing leaves from a tree, cherry or otherwise, but a small child might put something in their mouth.

Children are very unlikely to come into contact with or eat wilted wild cherry leaves, so it’s probably a moot point. But the chemistry is there to harm or kill them, certainly, if they did eat a sufficient quantity.

Had a tree trimming crew leave the branches of some wild cherry along the fence in a pasture. The crew were city dwellers and had no idea of the problem about the leaves of the cherry trees. Cost us 4K for the 4 steers that were killed, all Black Angus and about 1100 lbs. apiece. We got off lucky as this was in 1977 and beef was a little cheaper then. Now I understand it is standard training for the line clearance crews whenever working near farmland.

Thank you for telling us of your experience.

Why does the wilting make a difference?

Wilting is not absolutely essential. However, in a healthy tree, the component compounds that produce cyanide are isolated from each other. Chewing the leaves, or damage to the tree, such as a tree or its branches falling in a storm, produces damage and a combining of those components. The leaves of such a tree typically are wilted. When raising livestock, it is best not to have any of such trees growing where the cattle are likely to be.

Prunasin, the cyanide-containing molecule of the black cherry leaf, is neither destroyed nor altered when the leaf wilts. The completely healthy leaf and the completely dried leaf contain prunasin. Wilting occurs when a leaf losses water and, If unchecked, dries to a brittle state. The cyanogenic potential of the leaf does not change during this process.

To liberate cyanide gas, the dried leaf must be crushed and mixed with water; the intact leaf, just crushed. Crushing results in prunasin mixing with an enzyme also found in the leaf. This mixing initiates a process that leads to the liberation of cyanide gas. A second compound, benzaldehyde, is also produced at the same time. Benzaldehyde has the distinctive odor of bitter almonds and at room temperature becomes noticeable 15-30 seconds after a fresh leaf is crushed. If you smell benzaldehyde you are inhaling cyanide.

To see a demonstration of the killing power of the dried leaf of the black cherry: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fj7q5ORjxkg

For more information: https://facultyweb.cortland.edu/fitzgerald/three%20caterpillars.html

[…] Wilted cherry leaves kill – Quirky Science […]