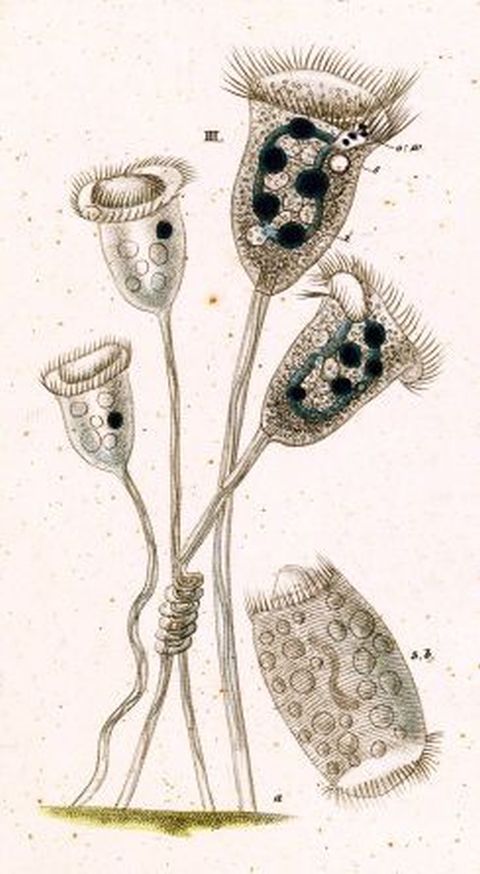

That pull rope is actually a fibril or stalk called a myoneme,1 which has, running down its middle, an internal organelle. This spasmoneme contracts into a spring or corkscrew shape, as seen in the video below.

Why is Vorticella of Interest

Scientists are not ashamed to learn from the lowly creature. The contraction and elongation of its stalk appears to depend on the binding and re-release of calcium ions by the protein spasmin.

What makes this of special interest is no ATP (adenosine triphosphate) is necessary to achieve the task, though ordinarily, it plays a vital role in muscle function.

High Tech Plumbing?

Curiously, it has been suggested this calcium mediated extension and contraction might be useful in a flow regulation device. Such a controller would allow increased or decreased flow, based on the bodies of the creatures, extended or contracted.

Their bodies are manipulated in the prototype through the addition or removal of calcium ions. This is achieved by means of an ion depleting agent (chelator). Yet, muscular extension and contraction via calcium ions is not the only interesting feature of vorticella.

Adhesives

When vorticella reproduces, its single stalk is not divided. At least one of the sister organisms relocates to attach itself via a new stalk. Its adhesive, unaffected by water, may lead to developing superior underwater adhesives. The use of such would make it unnecessary to remove the object from the water in order to repair it.

Waste Management

Vorticella bears three rows of minute hairs called cilia that are capable of sequential or wavelike movement that draws bacteria into its oral cavity. It also consumes algae. Thus, it is one of the most desirable life forms found in wastewater treatment plants.

1 A schematic image of the myoneme, including the spasmoneme, can be seen in this MIT hosted article.

Note: You might also enjoy Daphnia Pulex: The Water Flea

References:

- University of Florida: Mechanics of Vorticella Contraction

- Jstor: Collection of Food by Vorticella

- Harvard University: Observing the Ultra-Fast Contraction of Spasmonemes