Spicy hot peppers can provide culinary delight, or gastronomical torture for those with sensitive stomachs. So what is it – from a chemistry perspective – that makes those hot peppers so hot?

Hot Peppers Contain Capsaicin

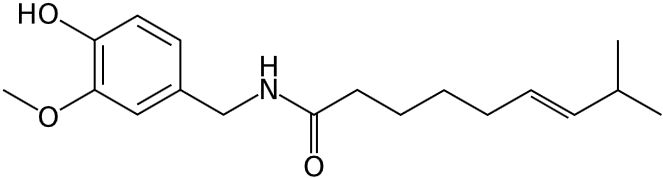

For simplicity’s sake, we’ll limit the scope of this article to a single hot pepper constituent: capsaicin (IUPAC chemical name, (E)-N-[(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-8-methylnon-6-enamide).

Scientists assign capsaicin in pure form a Scoville heat value of 16,000,000.

The Scoville value is subjective. Raters determine heat by means of tasting increasing dilution of pepper solutions.

The jalapeño pepper, for example, possesses a Scoville rating of up to 4,000, while a habanero pepper rates at about a 250,000 on the scale.

By comparison, a ghost pepper has a rating of up to 1,000,000. Hot enough?

Still hotter is the Carolina Reaper, registering an amazing 1,500,000 to 2,000,000 Scoville units. Peppers so hot, it takes an “insane” person to want to eat them?

What is it about such peppers that “turns on” the heat?

Before we answer that, let’s briefly discuss the chemistry of capsaicin.

What is Capsaicin?

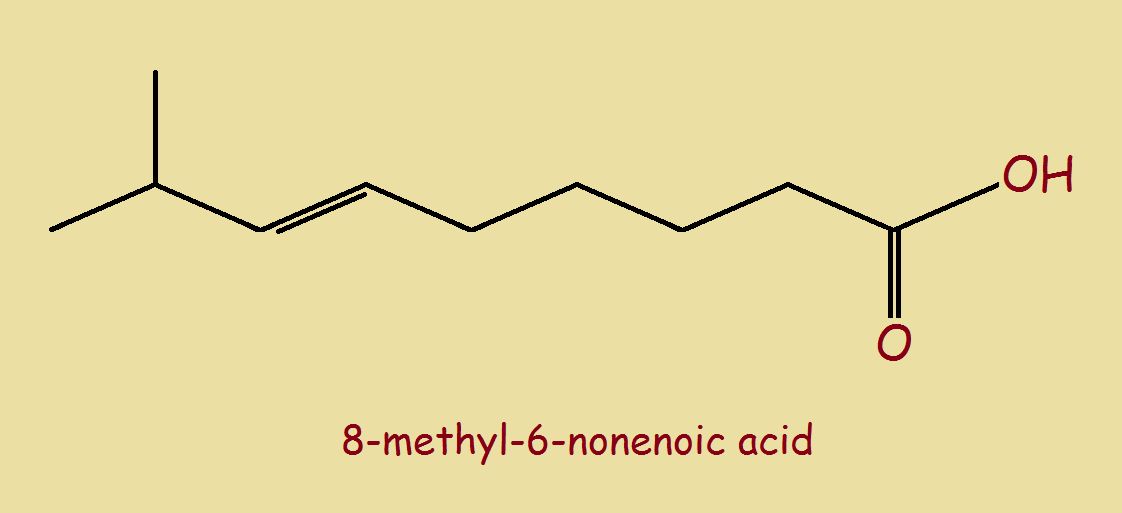

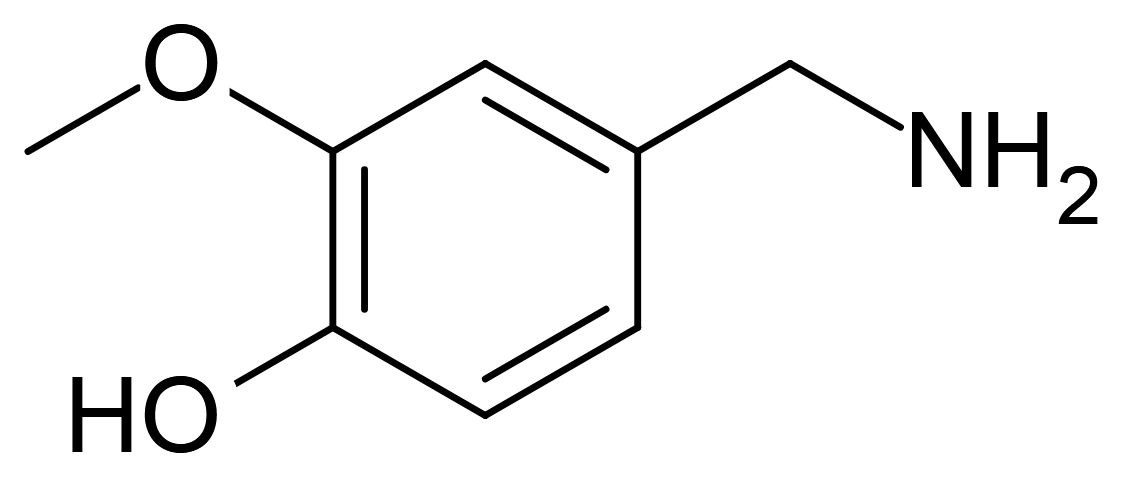

The pungent organic (carbon-based) compound, capsaicin, is essentially a vannilylamine molecule (related to vanilla) combined with 8-methyl-6-nonenoic acid to form the amide.

To the uninitiated, this would seem a combination unlikely to result in an intensely hot taste, as vanilla is not hot – but to the chemist, it makes perfect sense.

Structurally, the chemically reactive groups within a molecule of capsaicin include ether (–COC–) , alcohol (–OH), amide (–CONH2–) and alkene (–C=C–) linkages.

What gives this simple chemistry so powerful a taste is capsaicin’s reaction with so-called transient receptor potential channel sensors (TRP) – in particular, the TRPV1 sensor.

TRP Channel Sensors

TRPV1 is sensitive to certain chemicals, most notably the vanilloids (compounds resembling vanilla – hence the V in TRPV1). TRPV1 is a cationic (positively charged ions) channel sensor; an algogenic (pain-producing) protein.

It functions as a polymodal sensor, meaning there is more than one way the sensation of pain originates. Excessive temperature triggers pain. So too, does the ordinarily non-damaging stimulant capsaicin. The pain that the capsaicin produces is mediated somewhat by an influx of extracellular calcium ions.

Research is ongoing to discover all of the nuances of this relationship.

Does Capsaicin Enhance Flavor or Serve as a Warning?

The answer is Yes, on both counts.

Since capsaicin does not ordinarily damage the body, but in great excess can kill an organism, the question arises, is the capsaicin and TRPV1 mechanism designed to warn us that hot peppers are dangerous, or does it merely inform us when we’ve achieved the correct heat?

Let’s first consider possible advantages to including capsaicin in our diet.

Benefits of Consuming Capsaicin

There appear to be a number of health benefits from the responsible eating of capsaicin-containing food.

Hot peppers are helpful in reducing heart rate, blood clotting, insulin level, and free radicals. This is because hot peppers are rich in vitamins, minerals, fiber, phytochemicals, and antioxidants.

Additionally, a good healthy dose of peppers can help regulate body weight by lowering appetite, raising body temperature, and burning fat calories.

Curiously, although capsaicin is best known for its ability to inflict pain, when made into an analgesic cream, it has actually been used in the reduction of pain, such as that experienced by arthritics and post-operative patients.

A Beneficial and Chemically Interesting Substance

Capsaicin may be the hottest part of your next meal – even if the dish is served cold. This interesting chemical can soothe arthritis pain as well as spice up a curry – and it’s all due to a chemical structure that’s related to vanilla, of all things. Chemicals: they’re what’s for dinner – your dinner.

Note: You might also enjoy Chemicals to Peel Tomatoes?

References:

- Story, Gina M, et al. Feel the Burn. (2007). American Scientist

- Cortwright, Daniel N, et al. ScienceDirect: TRP Channels and Pain. (2007). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta

- Patterson Neubert, Amy. Reasonable quantities of red pepper may help curb appetite. (2011). Purdue University News Service

- Cox, Myles. University of Vermont: Welcome to the Spice Age. (2014). UVM Food Feed

- Mdowik, Melissa. Enjoy the Health Benefits of Peppers. (2013). Colorado State University

- usHOTstuff.com: The World’s Hottest Chili Peppers

← Back to Food and Health

← Home